In which Pawn finds some faith, views lots of art, and uncovers a whole new set of questions, all within the realms of Whitechapel an Southwark. Humbled and newly considered, he shutters in and tries to cure his head.

Pawn’s new friend Anne has thoughtfully furnished a list of East End art gallery recommendations which promise to pull Pawn back to the East and his father’s old stomping grounds. Previous visits to London have consisted of little time in the East End, other than theatre outings to Hackney, and last year’s stumble through Stepney (and Whitechapel, Bethnel, Bethnel Green, Stepney Green, Limehouse, Mile End…) was more a journey of familial rediscovery than a romp through the most vibrant arts community in Europe. Thanks to Anne’s able guide, I intend to change that this time around.

Since most of the private galleries are shut Tuesdays, today lead to the recently reopened Whitechapel Gallery. Whitechapel was the progenitor, the original gallery of 20th century art, opened in 1901, and its 1914 exhibit on 20th century works set the bar for all contemporary art museums to follow. It has had various face lifts over the years, most recently in 1985. This last refinish saw the gallery closed for a few years while it was completely revamped. The results are breathtaking. The gallery spaces are large and airy, with plenty of natural light and a high state of finish.

The exhibits in right now are quite broad and diverse. Isa Genzken: Open Sesame examines the works of this sculptor over the past 40 years. Goshka Macuga: The Bloomberg Commssion explores the intersection of political, social and cultural spheres, specifically in re: Guernica. British Council Collection: Great Early Buys shows off some of the important early acquisitions of this important cultural force. The Whitechapel Boys traces the history and early works of the driving force behind the arts scene in Whitechapel of the beginning of the 20th century.

Let’s look a little bit at each. Isa Genzken had a prolific career, and has certainly had an impact on other arts over the years. Some of her works show a vital curiosity about space and massing which is almost more architectural than sculptura:

I found it interesting more for its historical import than as art. I must confess a certain ambivalence towards much in 20th century art, which begs the question, you may well say, why am I celebrating a contemporary arts gallery? Because it is still very important in the greater scheme, and while there is much I am ambivalent about, and much which leaves me cold, there is also much which I find engaging, vital and inspired. In the case of Genzken, I am able to enjoy some of it, some informs me, and some just doesn’t get there. Onward.

Goshka Macuga has used the Blomberg Commission to create in Gallery 2 (until April 2010) a combination art exhibit, educational forum and library, all dedicated to the famous Picasso piece, Guernica. While not showing the actual Picasso creation (which was displayed at Whitechapel back in 1939) it does proudly feature a 1955 tapestry rendition created by Jacqueline de la Baume Düurrbach (with Picasso’s coöperation) at the far end of the gallery space. This tapestry has hung in the United Nations press gallery for the past 24 years. Nearer to the door one finds a film on the violence of war. Inattentive visitors may not notice that as they sit to watch this their feet rest upon a hand woven rug which is itself a map of the staging of military material in and around the Iraqi theatre of operations.

Opposite the film is a bronze bust of Colin Powell, done by Macuga in a Cubist style. The bust captures that moment, now of profound embarrassment to Powell, where, during the 2003 run-up to the US lead invasion of Iraq, Powell addressed the United Nation to make the case for war. In this frozen moment Powell is holding up the famous “vial of nerve agent” which he assured us Saddam Hussein was manufacturing in the notoriously missing mobile chemical facilities. This is a fascinating piece in its examination of the lowest point in the much celebrated career of a dedicated public servant. Macuga does have a reverence for Powell, and it comes through in her tender treatment of him.

The centre of the gallery is a large round display table in which are displayed various artifacts of Guernica, the importance it played in the Spanish Civil War, and in the rallying of public sentiment against Fascism in the years before World War II. The history of Whitechapel Gallery, Picasso and Guernica are also explored through old correspondence related to efforts to bring the piece back to Whitechapel after its important showing in 1939.

British Council Collection: Great Early Buys invites a series of guest curators to comb through the over 8000 items in this largest of collections of 20th century British art to select those pieces which they feel reflect the best in the early acquisitions. Prominent in this exhibit, the first of five to be displayed over the next 12 months and curated by Michael Craig-Martin, are works by David Hockney, Peter Doig, Chris Ofili, Lucian Freud, Paul Nash, Ben Nicholson and Gilbert & George.

This is one of those exhibits which just must be seen. This is one of the great collections cleaning out the larder and showing works which otherwise have no home. The British Council Collection have no regular home, and serves primarily as a lender to other galleries and museums across the globe. To have this collection thrown wide open via that gallery which was founded on appreciation of 20th century work is fitting indeed.

I may have to come back before the last exhibition has closed to see what one of the other guest curators come up with. Five stars!

Lastly come the Whitechapel Boys. This exhibit honours those artists who rose up out of the Jewish diaspora who settled in the East End in the late 19th century and lead the foundation of British Modernism. We are speaking here of David Bomberg, Jacob Epstein, Mark Gertier, Jacob Kramer, Clare Winston, Stephen Winston and Alfred Wolmark, amongst others. This is not a very broad exhibit, showing maybe one or two pieces by each of these. There are also a handfull of display cases showing notes, doodles, studies and publications.

The exhibit shows us how this group, many of them either first or second generation immigrants who had fled the anti-Semitic pogroms of the era which had swept Eastern and Central Europe (and which lead to the immigration to this very neighbourhood by Pawn’s own ancestors) developed a new vernacular for the 20th century right as the institutions which would foster that art and inculcate it began to rise in their midst. Indeed this exhibit has the feel of a celebration of life of a favourite friend of Whitechapel Gallery. We see how this group came to prominence along side the gallery’s own emergence as an important force in this new art.

I would call special attention to Clare Winston’s (Clara Birnberg) 1910 Art Deco masterpiece Attack which offers a vivid and piercing rendition of the violence of war which would make a fitting companion to Guenica. Also, Jacob Kramer’s 1919 Day of Atonement represents an important introduction of the visual vocabulary of traditional Jewish artwork into the modern vernacular. To have these pieces on display together is brilliant.

As I took leave of this gallery, I found it had a profound affect on me. I have never really thought about my father’s taste in art, or his interest in it. My relationship to him revolved around our peculiar shared interests in building things, making systems work, understanding the insides of machines, electronics, computers. I never knew him to have any deep appreciation of art, though to think he did not seems absurd, in retrospect. He grew up surrounded by this new modernism, but still fully immersed in the traditional arts of his people and his home.

This new question burns still in my soul, I have a new curiosity I must find some way to satisfy. Perhaps some other family member (most likely older sister) will hold some keys to this. Hmm.

A further stroll though the neighbourhood around Whitechapel Gallery freshened my mind and lifted my spirit from the must and violence of the old wartime art. Then hopped the tube over to Mansion House station and a stroll across the Millennium Bridge to the Tate Modern. May as well overdose, don’t you think?

In keeping with my general fecklessness, I managed to just miss the Rodchenko and Popova exhibit: Defining Constructivism. In fine form, it closed two days ago. Oh well, last year is was Duchamp and Man Ray I had just missed, and this time it is their contemporaries, Rodchenko and Popova. No fuss, there is plenty to see here, and I was particularly interested in seeing Roni Horn: aka Roni Horn open through next week. At least I made it to this one!

Roni Horn uses a variety of media and styles to explore the lines between self and surroundings, that porous border region between who we are, what we are and where we are. She likes to tease the edges of what she calls androgyny in which she means not just the traditional definition of that which is neither male nor female. No, she means that which is more generally neither one thing or another. An example is Asphere, which appears at first glance to be a simple metal sphere until, on closer inspection, we see it is in fact slightly un-spherical. Horn, The exhibit guide informs us, says “Asphere is an homage to androgyny…It gives the experience of something initially familiar, but the more time spent with it, the less familiar it becomes. I think of it as a self portrait.”

As this post is already so dreadfully long, so was my art viewing experience. I did find much more to like in the Horn exhibit. Her photo series, in particular, held my attention. Cabinet 2001 a series of 36 prints of a clown in bandages, for example, or Pi, a set of 45 images displayed on the four walls of a single gallery, and draw the eye around from one to the next with a consistent horizon through all images even though these are a mixture of landscapes, portraits, bird’s nests and other images.

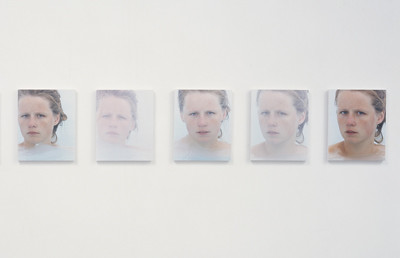

Lastly I must mention You are the Weather, 1994-95.

This is a series of 100 photographs of the same model gazing directly into the camera while in a series of pools all over Iceland in all sort of weather. We see changes in the expression and demeanour of the model as we meet her gaze time and time again. As Horn explains, these changes in demeanour, reflecting the weather conditions of each shoot, put us in the place of the weather – by meeting our gaze it appears that the model is reacting to us, thus You are the Weather. It is a well made and well presented piece.

Before leaving Tate Modern for a night resting up and home, I took a spin through the rest of the regular and changing exhibits. I won’t detail them all hear but I will say that I may have reached the end of my patience with Cubism. Tate Modern have a wonderful collection of Picasso and it was a pleasure to see so many of them. Along with these are Madigliori, Klee, Kandinski, etc. etc. etc. I love them all, but gallery after gallery of Cubism, good and bad, is just too much (yes, I know, those aren’t all Cubism, I’m just saying I like the bulk of the collection). Especially when they are simply crawling with students from Holland, France and Germany all sitting on the floor or slinging around their rucksacks or slouching around corners to snog – and scribbling in notebooks the whole time.

The winds continued today, unabated, and with them my allergies have been exacerbated. Tomorrow they are due to die down, which will be a relief. “I hope the wind dies down. Its very trying.” wrote Anne yesterday. I couldn’t agree more. One thing about the winds here which are quite different from the US is that, as England is essentially an island, high winds mean rapid changes in barometric pressure and humidity conditions. So, the day can go from bright, dry and sunny to pouring rain in a heartbeat. And back again. This happens on and off all day long, so you must have your brolley handy, or just accept that you will get wet.

Oh; yesterday was a work day, with only a brief visit to Hyde park for a walkabout by the Serpentine and the Long Water (see gallery here) and a visit to the Serpentine Gallery for film works by Luke Fowler and other exhibits. Not much that really moved me.

All for now,

Ta!