I’ve just come from seeing the Divadlo Dlouhé’s production of Henrik Ibsen’s Heda Gablerová. This is the first time I’ve gone to see theatre in a foreign language without some sort of translation services — supertitles, subtitles, assistive technology (audio or visual) — and it was kind of a trip, but more so for how the piece was presented than for the language barrier.

I know Hedda Gabbler very well. I stage managed a production in college, lo those many years ago, which entails memorizing the entire script (not just one part). I’ve seen film versions of it; saw Milwaukee’s own Theatre X present it 35 years ago, saw a production in Amsterdam the summer of 2016 (supertitles). I know the story, so wasn’t really lost in the words.

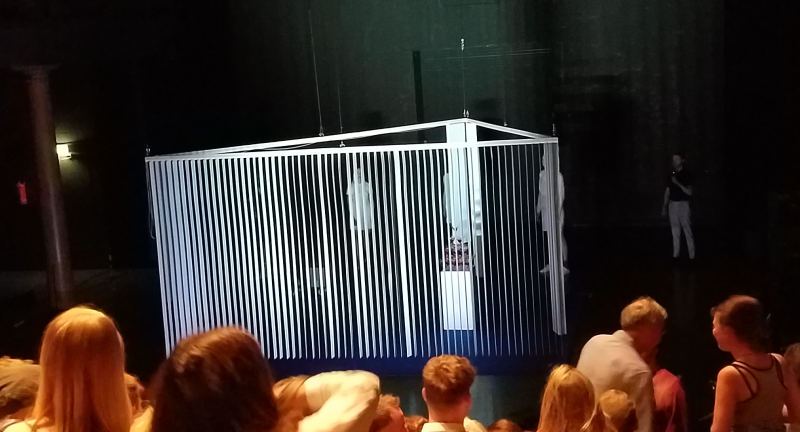

This lovely little theatre is just a 6 minute walk from the flat, so easy-peasy. I got there early, paid less than $15 for my ticket (320CK) in the 6th row, center. The stage was stark. One set, a sitting room, with an exposed lavatory upstage right and another upstage left. There was a table mid-stage, some “pit group” type seating downstage right and a patio lounge chair downstage left. A Lexan (Perspex, Plexiglas, what have you) wall defined the back of the stage, a large projection screen above it. A digital clock displayed in the top corner.

Another Lexan wall divided the stage left from right, about two thirds of the way over from stage right. The table pierced this wall, half on each side of the stage.

I already got the metaphor.

Ibsen is famous for a couple of things. One is for being the first playwright to focus on total realism in his text and settings, his characters and their lives, even in the realization of his productions; sets, lighting, costumes, etc. All was to be as real as possible. The other is that he almost exclusively wrote about the sorry lot of women. His leading characters are women, both in Hedda Gabbler and The Doll’s House. Like his fellow Swede, August Strindberg, he saw great unfairness in the roles society allowed women to hold, and he pushed back against these in his plays.

Hedda is a fierce creature, she grew up the pampered pet of her strong and important father. Now she is married off to a bumbling professor of philosophy and bridles at the restrictions of married life. She has always been the one in control with the men in her life (and there have been, continue to be, a few) and just cannot stand the wifely role of subservience and home life.

The smaller, side of the stage, the right, from the audience’s perspective, was for Hedda. The large space was for everyone else.

In the production I saw in Holland last year, a similar effect was created by the brilliant set design which was a triangular prism defined by three huge vertical blinds. A prism which was a prison. All the characters besides Hedda could walk in and out of this space, but she was forever held within it.

So yeah, I got the metaphor. It seems nobody can handle Ibsen without steeping the whole thing in metaphor. Well, hang on, there’s a ton of it here.

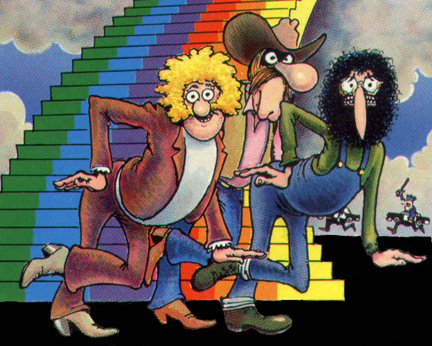

In case you hadn’t noticed, the men in this Czech production are all presented as effeminate buffoons. They’re like a middle-aged, cross-dressing version of the Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers of the old comix.

As for Hedda, while she starts out in a shift, she’s soon wearing pants, and for the remainder of the show.

The production design is like David Lynch collaborated with Eddie Izzard, with a little R Crumb thrown in for effect. There’s the strange omni-present lady upstage, behind that Lexan wall, who serves as a narrator of sorts, a few times during the show, while changing from a “slutty nurse” outfit to sailor duds and then nun’s habit.

Hedda’s relationships with all and sundry are played with the wall always, well almost always, between them. Whether it’s an intense lesbian S&M scene with Tea Elvstedová, the fiancée to her former lover (and husband’s protégé) Eilert Løvborg, played across the table.

Or the flat out (or flat up) sex scene between her and that same ex-lover

By the end of things, however, all of these men are stripped of their feminine finery, either literally, in the case of Eilert, or have changed in to (mourning) suits, like Tesman, Hedda’s husband, or Judge Brack, the gadabout.

You see, Hedda, trapped in her marriage, pregnancy, society…feeling powerless, exercises what power she has by preying on and playing with those around her. She ruins who she can, but ultimately is ruined by them and herself.

The downstage stage lift provides near tectonic effect, and a final resting place.

This was a splendid production all around. The costuming was cartoonish, almost too much so, but grew more and more somber as the evening progressed. The performances were brilliant, and I can say that without having understood more than “yes,” “no” and “please” (“ano,” “neh” and “proseem”). Lucie TrmÃková was downright bewitching as Heda, and I could have watched her all night long. Robert MikluÅ¡, as Eilert was amazing. The rest of the cast shone just as bright.

The visual effects — videotext scrolling by, with various language’s versions of the seven deadly sins; snow falling; big, bold comic book style “Bang” and such — not so great, but certainly not a defect. The lighting was effective without being intrusive, which could have easily happened. The set, all metaphor as it was, worked well.