Abramović, Kentridge, Cartier-Bresson, Burton. Those four faces of artistic expression lay in waiting for us at MoMA as we polished off our street-corner gyro, X and I, and dodged slow moving taxi cabs and ducked into the portico.

Oddly enough, it was Tim Burton, the exhibition of his sketchbooks, models, props and ephemera, which triggered this particular foray into New York. I wanted to see the show, and it closes on the 26th. The rest, Martina Abromovic, Henri Cartier-Bresson and William Kentridge, were icing on the cake, as it were. Or, in the case of Abramović, flesh upon the wall.

William Kentridge creates images and animations which are familiar to me, but I will confess a complete ignorance of his work, or the volume of it. Kentridge makes large drawings, typically charcoal and chalk on gauche and paper, sometimes segmented and articulated, and then films these pieces frame by frame to animate short films. Several of these films were exhibited here, in William Kentridge: Five Themes, which covers his entire career of 30 years. The show is expansive, but many of the films were hard for me to watch; the jittery nature of his animation, splayed across such large screens bothered my eyes, so I mostly focused on the drawings hung in the central galleries.

My favorite part of the exhibit was Kentridge’s animated theaters. These are complete theaters, typically about 6 feet wide and 4 or 5 feet tall, with carefully arranged and assembled tracks and guides and flats and frames and… very hard to explain here. Small automatonic figures enter and exit a stage defined by framing flats which are illuminated by projected set decoration. Again, too hard to describe with any grace here, but they were lovely.

Martina Abramović is a performance artist whose work tests the extremes of public acceptability. Over her long career she has produced many installations, pieces in which she creates a setting, sometimes grand, sometimes banal, in which she places herself or other “performers†and compels us to look on as some strange part of the human experience is put to the test within the little diorama she has wrought. “Martina Abramović: The Artist is Present,†is both a new piece and a retrospective of her career.

The titular piece is an installation in the Marron Atrium, a high ceilinged large open room on the museum’s second level. The artist is seated in a straight-back chair with a simple table in front of her. Across the table is a matching chair, in which visitors may sit, confronting the stoic, silent, artist. She sits thusly for the entire day (with careful proviso that she will not be present during late exhibit hours) from before the museum opens till after it closes. There are carefully arrayed hash marks on the wall which keep track of how many days she has been doing this (the show runs for about 10 weeks).

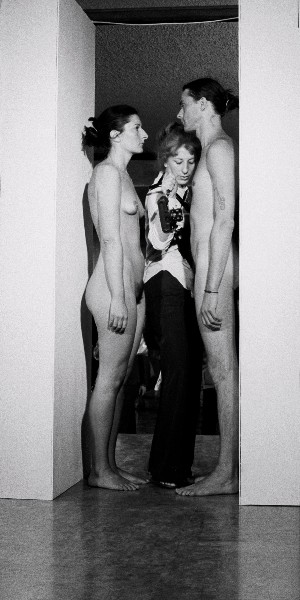

The sixth floor galleries bring us the retrospective of her work, covering her over 40 year career, with more than 50 pieces. Some are presented as films or videos, some as still photographs. The real import of the show, however, comes in the reënactments of many of her most important installation pieces, with a cast of performers taking on the roles that were always only filled by Abramović or her onetime partner, Ulay (Uwe Laysiepen). Here you may find a man and a woman, seated with their backs to each other, their hair braided together. Or facing each other, each pointing an accusatory finger at the other, for hours on end. A woman lays upon a plinth naked, a skeleton draped across her. Two women stand naked on either side of a doorway, challenging the visitor to pass between them.

It goes on and on, example after example of self indulgent, “let me offend you†work. The same theme seems to repeat in endless variations until the audience is numbed to it. The very in-you-face nature of the work seems in tension with the shear volume of it in this exhibition, which suffers the fate that so many retrospectives do at MoMA – over saturation. We just get bombarded with so much of these images that we become desensitized to them. One of Abramovićs works would have the desired effect upon most visitors (those who aren’t just offended and turn away) but 50 of them simply turn pale by repetition.

Okay, so I didn’t really like that show. What can I say. Time to move on to Henri Cartier-Bresson: The Modern Century. I am quite a fan of Cartier-Bresson, whose work is well featured in the current Street Scene at MAM. In this exhaustive, and exhausting, retrospective over 300 of his photographs, spanning the globe and many decades, covers his entire career. Three hundred photographs in a labyrinthine gallery packed with about 800 visitors at a time, many of them reeling from the Abramović experience as I was. Yeesh!

My complaint about curatorial under-selectiveness stands here as well. The trend at these shows seems to be that of quantity and completeness without any regard for how the visitor will appreciate the works and for the physical reality of getting through the show. The galleries sprawl, and while there are thematic groupings – Encounters; Beauty; Old Worlds, India; New Worlds, USA – these groupings themselves may be so large that one has a hard time discerning their start or end.

The work is fantastic, and where I would cut, I cannot say. Cartier-Bresson, as much as anyone, established the formal rules of editorial photo-journalism, and then routinely broke them. He practiced journalism but also portraiture. He had an eye for the moment, but also a mastery of composition.

The show is overwhelming, but worthwhile. A visit to MoMA just to see this one exhibit could take an entire afternoon, just to do it justice.

A respite in the sculpture garden was in order after the outright saturation of the past three exhibitions. We found a couple of chairs out of the sun, near the fountain, and just enjoyed the lovely weather. Ahh…

Okay, back to work! Tim Burton has had an interesting career spanning several decades. Popping onto the pop-culture scene with 1985’s Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and 1988’s Beetle Juice and continuing to the recently released Alice in Wonderland. I love his twisted imagery and wild imagination, as reflected in such masterpiece films as Mars Attacks, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, and The Nightmare Before Christmas. This exhibition brings together ephemera from his films – the angora sweater worn by Johnny Depp in Ed Wood, the cat suit worn by Michelle Pfeiffer in Batman Returns, fifty or so Jack Skellington puppet heads from Nightmare – and his artwork, sketchbooks, student films, etc. going back to his childhood in Burbank, CA.

This is a popular exhibit, one requiring timed admissions with pre-purchased tickets (good luck getting one day of show) and it is thronged. The show itself was a lot of fun. It was quite entertaining to hear young people, teens or tweens, explain to their parents who some of the characters from the recent films were – Corpse Bride, for example – while then hearing a parent explain who Beetle Juice is a moment later.

This was well worth the visit, and it was wonderful to get a peek into the work and vision behind the stunning visuals which make up so much of Burton’s work.

All in all a great day at MoMA. In many ways I have only myself to blame for the excesses of today’s visit. To be fair to the artists and their work, today’s visit should really have been broken into two or three visits. But, for a traveler, time is of the essence! Move on, more to do, and too little time!

Pingback: London Journal, A November Week | Fortune's Pawn