A bit of a break has ensued since last we’ve written, but now that we’re back on it, here’s a continuation of Thursday, the 20th.

Following the advice of the shopkeeper from Book Arts Books, we strolled back down to the Shoreditch high street and Merchants Tavern for a lovely and extravagant dinner and cocktails: cauliflower croquettes, seared scallops, leek and bleu cheese tart and X had encrusted fillet of cod with creamed celeriac root. Yum YUM!! It helped, ho doubt, that we were being served some well made Martinis, which are a rarity here.

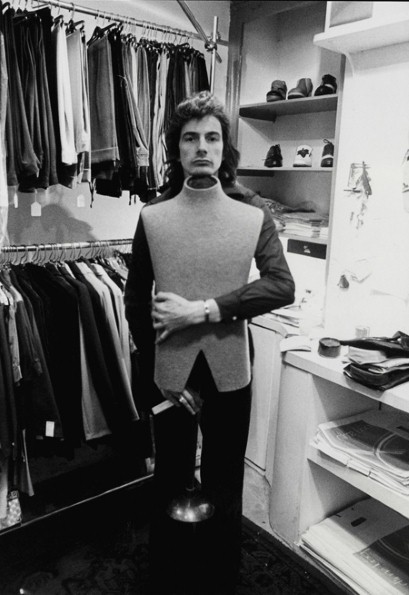

Dinner settled, it’s back to the theatre, a double bill of works by Doug Lucie. First up was a revival of Doing The Business, in which Peter (Matther Carter) a smarmy City Boy in a bright red tie and tight hip-riding blue flood pants held up by braces tries to explain to Mike (Jim Mannering) a grammer school chum newly in charge of a theatre company dependent upon Peter’s largesse, that if they would just make some changes (not compromises) to the company’s plans, there would be cash aplenty to sort their debts and deficits.

This is a taut play of speeches, mostly, with very little actual back-and-forth dialogue. Written in reaction to the draconian cuts to government arts funding in the late 1980s, this is a sermon preached to the choir. These two, while hard to imagine as schoolboys of the same cloth, have matured into archetypes of the most severe sort. Peter is smug and self privileged, father of two young girls, who are the receptacles of his only true charity. Mike is self righteous and suffering, with high-minded ideals uncompromised by the vicissitudes of real-world life.

While predictable in its story arc, the play none-the-less forces us to consider all of the issues involved with corporate grant giving and the necessary deal making that goes on alongside it. Of course we want to hate Peter and side with Mike (we wouldn’t be in the audience otherwise, would we?) but we see Mike willing to throw away his high morals when presented with the wealth he needs to achieve his (now lowered) goals. Despite the short comings of predictability and convention, this was a bracing piece of theatre. The performances were stunningly clear and utterly believable — we saw two characters on stage, but no actors — as it should be. The technical aspects of this show, as with Blind, are of workshop standards and not to be criticized one way or the other; they sufficed.

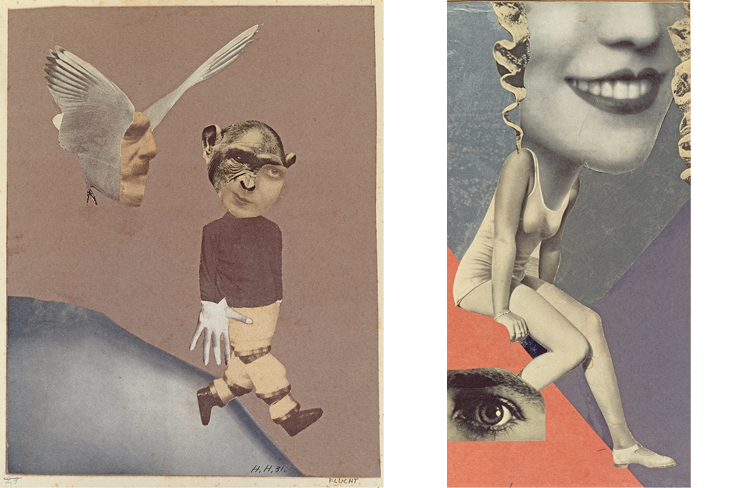

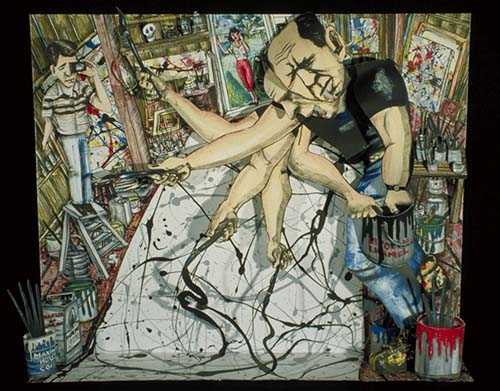

Blind, the second half of the double bill, is a newer piece, and has as its subject the interrelations between patrons and artists, and the differences between the commerce of art, the commercialization of art; between the valuation of art and the value of it; between a patron and a sponsor, a buyer and a dealer, a dealer and a market maker; between an artist responding to their muse and an artist responding to a market. This is diamond-hard naval-gazing for the truly ennobled artists among us; and a fun bit of drama for the rest of us around the periphery of that.

Alan (Cameron Harle) is a young artist put up in a studio he could never afford by his patron, Mo (Jon McKenna), an older man with an ill wife and a whole closet full of skeletons. Mo is sitting (nude) for a portrait and as Alan paints, we get the exposition to setup the story of Mo taking a liking to Alan’s work, and deciding to support him via the rental of the studio. We get a sense, too, of a bond, call it paternal, between them; Alan is an investment, true, but more of a spiritual than a monetary one, for Mo.

Maddy (Janna Fox) is an in-your-face artist-cum-anti-artist in the mould of Tracey Emin, and is making work of stark contrast to Alan’s classicist painting. Her’s is a denial of art (i.e. “turd in a teacup), more meta and conceptual, and her personality is half the story. Clashes with the press, insults slung across galleries at stodgy arts types, explosive addictions and abuse of all around her. She takes a liking to Alan, however, and introduces him to her sponsor, Paul (Daniel York) a smarmy, Charles Saatchi type, who eyes art with dollar (or pound) signs in his eyes, always thinking of how an artist can get him to the next market nexus.

As we know it must, a romance of convenience (for which side?) develops between Alan and Maddy just as commerce of convenience develops between Alan and Paul. Where does this leave Mo? A scene of conflict between he and Paul revealing the skeletons in Mo’s past (not as shocking as the playwright may have wanted) is quickly followed by a détente of convenience between Mo and Maddy, who is redeemed by her evident mastery of drawing (a conceptual artist with actual artistic skills, who knew?!?) and as the play comes to and end, we see the depths to which Alan has been drug by the devils he has chosen, Maddy elevated by her return to art’s roots, Mo on the verge of life changing events and Paul has simply vanished, much as the whims of the art world change from season to season.

It is dense and knowing, this work, and presumes both an acceptance of convention (and classical themes) and I dare say an agreement with Lucie’s interpretation of the validity of one take on the art world over another. While I enjoyed the night of theatre, I do not accept the false dichotomy presented therein. Art and commerce are inevitably intertwined whenever the artist seeks to make a living from art. This must be so, whether it is patronage or sponsorship or selling portraits in a market stall, commerce is commerce, trade is trade, custom is custom, money is money. If we monetize the creation of beauty, then we have commercialized it to one extent or another.

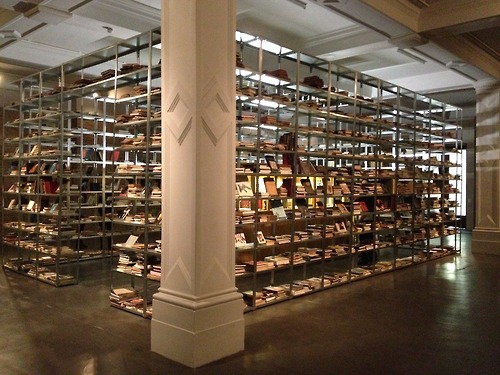

If an artist chooses to make art free of commerce, there is ample precedence for that — look at the vital world of what Pawn calls “Private Art”. Often classified as “naïve,” “self-taught,” “visionary,” or “folk” art, this may veer to the commercial (crafty art sold at tag sales) but is often conceived, executed and kept for the artist’s private use and enjoyment. Occasionally hoards of private art are discovered, brought to the world’s attention, and (often posthumous) celebrity rains down upon the artist. Henry Darger and Vivian Maier are prime examples of such private-made-public collections.

All in all, Doing The Business and Blind are fine theatre and represent an ambitious undertaking by Triple Jump Productions. The performances were all stellar. Jon McKenna was a breath of fresh air as Mo Dyer in Blind in that he was age appropriate, as is too rare these days from smaller companies. Daniel York brought just the right level of sneering smarmyness to the role of Paul Stone, and we hated him for it, as with Matthew Carter’s turn as Peter (the City boy).