The early bird gets the worm, or in this case the tickets. Following a typically fitful first-night’s sleep in travel quarters, Pawn was first to rise and after breaky of eggy~weggs and a rasher, with croissant and pot of forgettable coffee, was off blazing trails through Jubilee Park (home of the Eye) and across the footbridge to Trafalgar Square, the National Portrait Gallery and the same-day ticket queue for Lucian Freud Portraits, the enormous show (with some enormous portraits of some enormous bodies and some enormous egos) which just opened.

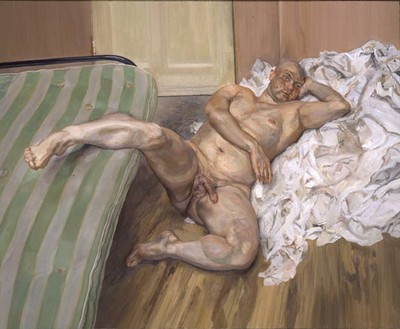

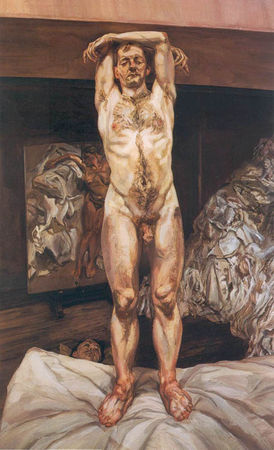

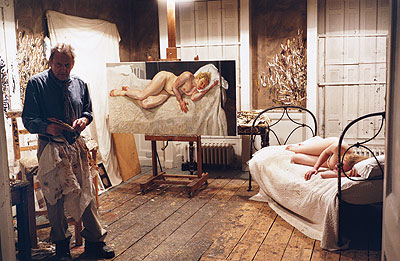

Lucian Freud - Evening in the studio - 1993

“…we tried going to that yesterday too! No luck. Our first ticket is 21 March… too many people in London.†wrote CP, yesterday, when I whined about a lack of tickets via the online ticket site.

Allow me a moment to rant about crap online ticket sites. This one, for NPG, is run by Ticketmaster, who with their monopoly and all you’d think would know how to run such a thing. But you’d be wrong. Their site is crap, and not at all easy to operate if you’re looking for an available ticket to a long-term event. One must keep drilling down into a date, and then back out again, with no opportunity to simply ask, “how `bout the next day?†Crap, utter, useless crap!

So with the gallery opening at 10, and the knowledge that they hold back tickets for same-day sales on-site, I head off and get on queue. Send a message to X, back at the flat (no comment here on her early rising record…). What I wrote was “Queuing for Freud: They’re saying 30 minutes but definitely tickets for today.†but what my inaptly named “smart phone†decided I meant was “Wiring for Freud…†Gotta love technology.

That was at 10:08. Turns out they had let people start queuing at 9:00, so I wasn’t exactly at the start of the queue, but by 10:33 I wrote, “close to counter. Will ask for 12:30 entrance time.†which would leave time for lunch prior to entering massive exhibit of massive portraits of massive people and massive egos. I’d been warned, “130 works! wow. Give yourself plenty of time for that one…†D wrote, jealous of my opportunity.

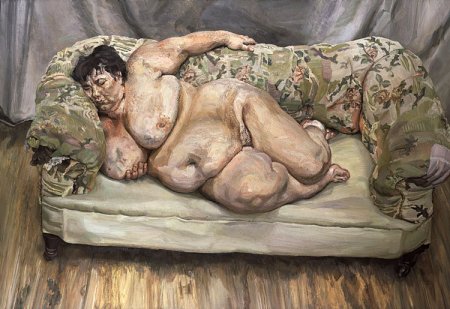

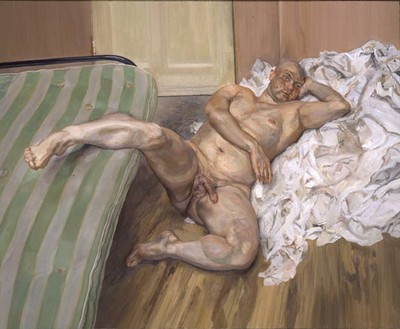

Lucian Freud - Nude with leg up - 1992

A few minutes later, tickets in hand, I strolled out into the BRIGHT SUNSHINE of Trafalgar Square and took my perch near the Fourth Plinth to wait for X to arrive fresh from her restorative ablutions. Lunch in a strange little diner (“MD’s where we don’t hide our ingredients behind a second slice of bread!â€) and then we’re in, in amongst some of the largest canvases of some of the largest naked bodies you’ll ever see.

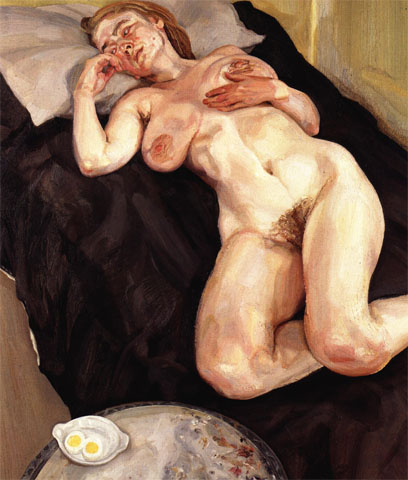

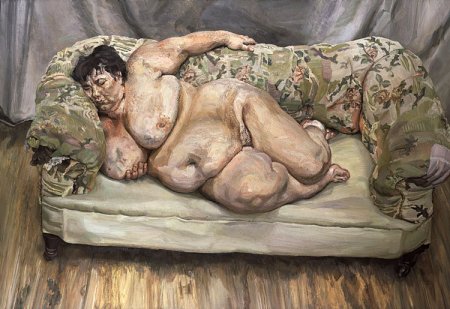

Lucian Freud - Benefits supervisor sleeping - 1995

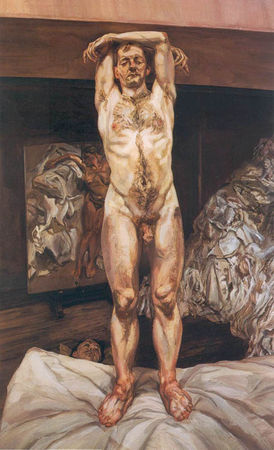

Okay, in all seriousness, it was a fantastic show. While it’s easy to joke about Freud’s willingness – hell predilection – to paint large people, that’s really quite beyond the point. What Freud has taught us, perhaps more than any other portrait artist, at least in the 20th century, is how to see the human form for what it is. Freud’s portraits are almost entirely de-eroticized, lacking any prurient aspect and though stylized, fervently true. He will worry a face or a shoulder or… anything, to the point of nearly obscuring it beneath the many layers of paint, but he will pierce through to the core of that thing, and that person whose thing that is.

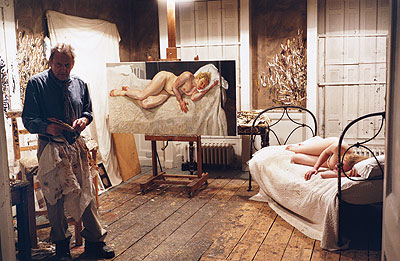

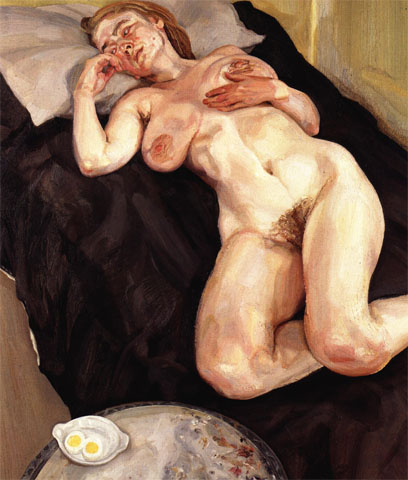

Lucian Freud - Naked girl with egg - 1980-81

Take women’s breasts, for example. Many painters (and photographers, sculptors, etc.) will pose their female subjects such that their breasts, if exposed, will be flattered, if not idealized. Freud, however, seems almost to strive for poses which show the breast in its most elastic, uncontrolled form. Pressed against the arm of a sofa, or flopped to the side, or cupped atop a sleeping subject’s arm. There is no romanticizing here, “Just paint it like I see it, “ one can almost hear him saying.

But the same fervour for authenticity carries over to all aspects of his portraiture – chins have waddles; foreheads, bony promontories; dimples, unflattering asymmetries; feet, bunions. Freud’s subjects, he tells us time and again, are normal people, just like us. When The Brigadier, 2003-4, sits for 200 hours for a portrait, Freud has him wear the same uniform he wore when he retired, some twenty years earlier after a victorious military campaign. An older man now, the uniform no longer fits as comfortably as it once did. The man cannot breath for these long, repeated sittings, so Freud suggests he unbutton the tunic. The result? The Brigadier’s paunch is prominent, it draws the eye, and what we see is not the idealized heroic figure, but the relaxed, retired and all too human man who lead others into battle and was brave or skilled or lucky enough to make it back in one piece so that twenty years later he could pose for this portrait looking like the relaxed, retired and slightly corpulent man that he has become.

Lucian Freud - The Brigadier - 2003-4

Freud has made us like this man, has found that part of ourselves, our everyman, within this man.

In his early work (which the exhibitors have thoughtfully but not rigidly arranged to make the most sense of an artist who’s work has matured as he has, not linearly but with parallel tracks, echoes forward and back, ripples which reflect off the mileposts of his own life) we see an artist who is working within constraints of the form as society understands it, before he begins to find his stride and his own true path. His wide-eyed portraits of the Girl in a dark jacket posed quite artificially, with unnaturally situated objects at once show him strain against the form of pose meets still life, yet also find new figurative language which suits him. He starts to break away in earnest with some self portraits, “Reflections†which are often truly that, from mirrors.

Lucian Freud - Girl in a dark jacket - 1947

By the time we get to the large commissioned and non-commissioned work for which he is best known, we are looking at iconic and iconoclastic work. There is no more Francis Bacon here, unless he chooses to show us that, there is no more of anyone else – just Freud and his models – even when the model is his dog, Eli.

Lucian Freud with Ria Kirby upon completion of Ria Naked Portrait - 2006-7

Something which merits mention is that until witnessed in person it is hard to appreciate just how much paint Freud slathers on to the canvas in his later work. In Ria Nude Portrait, 2007, the model’s right eye bulges out from the canvas so far she appears, under close examination, disfigured. Of course one doesn’t routinely view the great canvas up close and obliquely, so it may well go unnoticed. Faces, profound musculature, and genitalia are most likely to receive this treatment. I’ve mentioned already how de-eroticized Freud’s work is, and yet genitalia receive much attention under his brush. Women’s pubic areas are almost sculptural, three dimensional, in many of his works. Not surprising, perhaps, given his well earned reputation for prolific appetites, shall we say.

One last note, and then this essay shall close. Freud painted many self portraits, but his sense of reflection seems to go beyond this. When one considers the length of his sittings, into the hundreds of hours in many cases (some canvases took years) it’s easy to understand why he would make himself the subject so often, as he developed techniques or understanding. One thing which struck Pawn, however, is how often his own work figures in his work. He painted almost always in his studio, and often the studio itself is as much a subject as his models. It is not at all unusual to see one or more earlier, or incomplete canvases in a piece. For example, Two Men in the Studio, 1987-9, prominently features Standing by the Rags, 1988-9, made more interesting by the fact that the included painting was not started when the including work was.

Lucian Freud - Two men in the Studio - 1987-89

The Rags, of the latter pieces title, are well featured in both. Freud used recycled hotel linens for his paint rags, a fact which the unobtrusive but helpful exhibit text points out to us.

Lucian Freud Portraits is a exemplary exhibition, and well worthy of the crowds and praise it is thus far receiving. National Portrait Gallery have done themselves proud, and we were much the happier for having seen it.