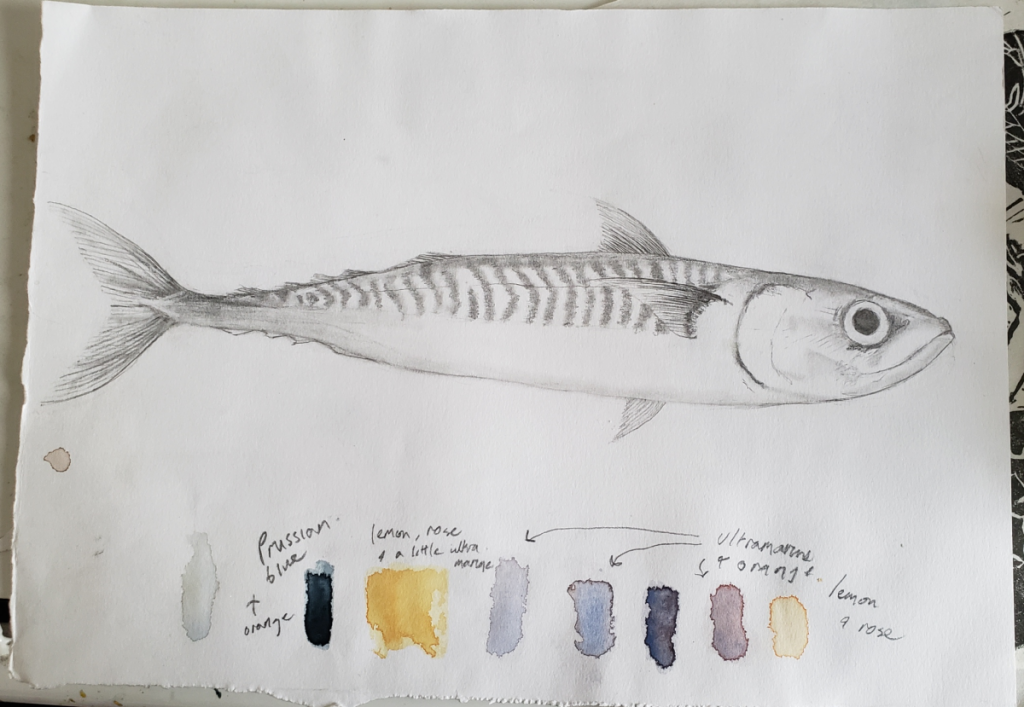

Day one and already out and about. J is happy to see me, and welcomes me into her home & studio. We haven’t seen each other in almost exactly two years, she being one of my last visits from my autumn 2019 stay. We catch up in her kitchen, tour her busy & messy studio, and then, following an intractable hunt for keys, are off to dinner at the De Beauvoir Arms, J’s local. I have lamb chops over an absolutely perfect mojadra, with celery and spinach, while J opts for the mackerel escabeche. Both meals very good.

Two of Pawn’s favourite places in London are Hundred Years Gallery and Bookarts Bookshop. The former in Hoxton, the latter by Old Street, not very far apart. Leaving with J from the pub, Pawn goes south towards the Kingsland Road and Hoxton whilst J has errands to run.

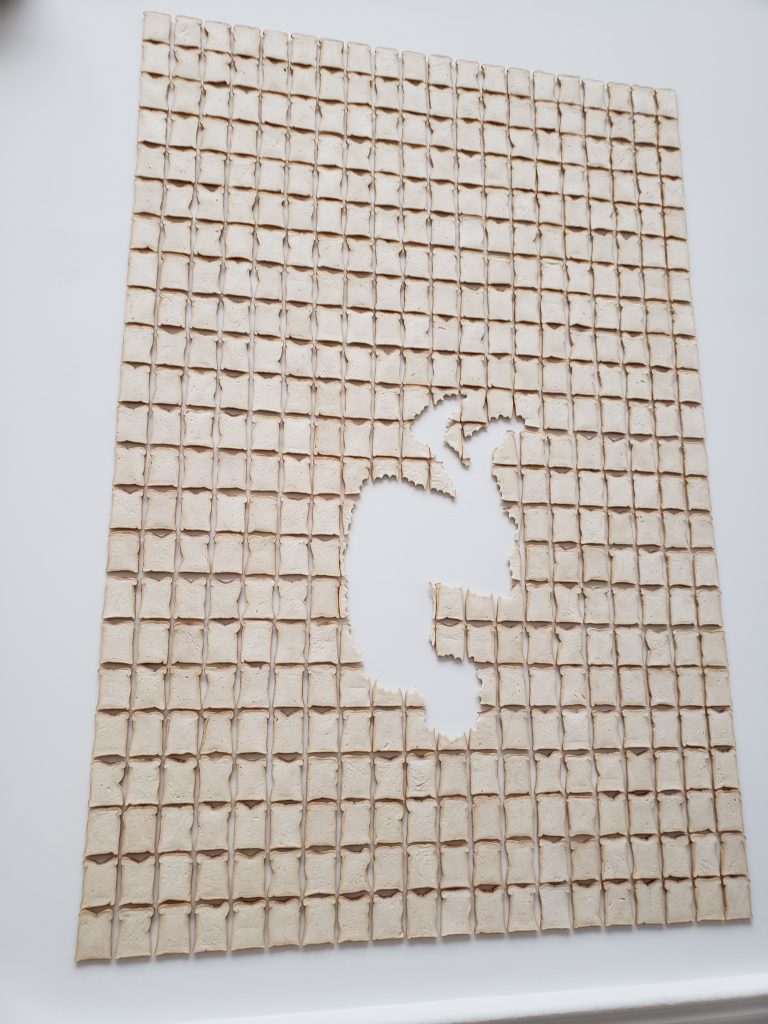

Hundred Years Gallery was open, as hoped, and empty, aside from G, the proprietor. Their current show is Nouns for Gabriel by Mary Lemley. This is a delightful series of large format sketches of objects the artist Mary Lemley has made for her autistic son, a suite of hand-made flash cards to help teach him vocabulary.

In the prints bin I quickly find several I cannot do without, and out comes the charge card. That didn’t take long. A bit more of a visit with G, and I’m out the door and winding my way down towards Old Street and Bookarts.

Bookarts Bookshop is a true gem. I’ve written before of its incomparable selection and broad reach. It’s a very tiny storefront on the corner of Pitfield Street and Charles Square, just north of Old Street tube stop. T, the proprietress and shopkeep, is likewise a gem. I had barely started to peruse the window display she had prepared for that day’s opening & book release party commemorating Thieri Foulc and the Oupeinpo movement, when, seeing me through the window, T waved her arms and beckoned me come in. In the small shop, perhaps three metres sqaure, she had erected a small table covered with books she felt I might like. T & I have similar tastes when it comes to artists books, hers being broader and more studied, to be sure.

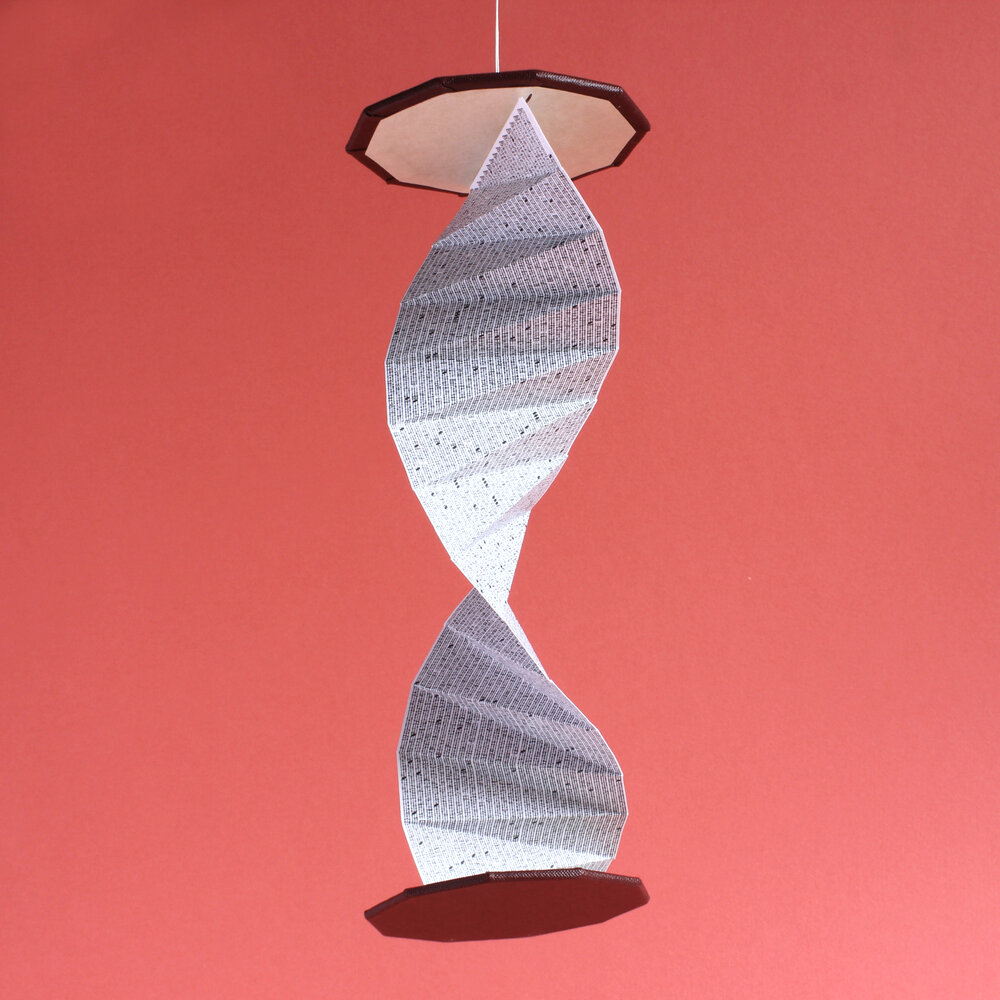

Quickly my hands alit on A Book for Spiders, by Tom Alexander. This is a beautifully hand bound, octagonal volume, with brown covers, roughly 7cm across, with a small white loop of thread piercing the top cover. Lifting this opens the book, which is a helix, called Missing Limbs, written in Vox Arachnae, for spiders to enjoy. A translation key is included within the craftily constructed outer wrap.

Mine is #2 of and edition of 10. T was beside herself when I grabbed this; the shop had received only two copies, and she had bought the other one herself. She was certain I’d want one. Other volumes making the cut were a Blow Up Press edition. I’ll be back for more shopping. This being an opening, there were soon several people in the small shop, and I had to step out to make way for them. In these COVD times, one doesn’t want to crowd into a small space with maskless folk, no matter how well read they may be.

And that concludes the evening. Back at the flat Pawn relaxed for the first two episodes of Ridley Road, the BBC four-part series on the Jewish opposition to English nationalism cum fascism of the early 1960s. My family left here in August 1963, while these events were still playing out. My father was a teenager in the East End (Tower Hamlets) during the events which came to be known as the Battle of Cable Street, years prior. One wonders how much the return of Fascists to London’s political life had an effect on my relocation to America. Had the fascists kept to themselves, may this entire trip not have been necessary?